Our first stop was the capital city of Beijing, known as Peking until the Revolution in 1949. After a recouperative night’s sleep following the 9 hour flight from London, I set off mid-morning to enormous Panjiayuan antiques market in the south east of the city. Although many flea markets are overrun with tourists, particularly in or near the centre of the city, this is more authentic and apparently many centrally based dealers buy here.

Our first stop was the capital city of Beijing, known as Peking until the Revolution in 1949. After a recouperative night’s sleep following the 9 hour flight from London, I set off mid-morning to enormous Panjiayuan antiques market in the south east of the city. Although many flea markets are overrun with tourists, particularly in or near the centre of the city, this is more authentic and apparently many centrally based dealers buy here.

The market compound is divided into two main sections, wide alleyways lined with permanent shops, and a truly vast open sided barn where sellers spread out rugs or blankets to display their wares for sale. I’m told that many are peasants who make their way into town after buying in the provinces, but I think most are really canny professionals.

By the time our taxi pulled up mid-morning, only a fifth of the space was still occupied – trade seemingly starts and tails off very early, and Saturday and Sunday are the best and busiest days. But there were still over 200 ‘stalls’, so the hunt was on. I had a good look round first to see what items were repeated across stands – obviously these would be factory produced contemporary pieces. Almost dizzy from the enormous selection, I spotted an appealing blue and white ceramic bottle vase at one stand, and a bright, three-coloured ‘Peking glass’ vase at another.

By the time our taxi pulled up mid-morning, only a fifth of the space was still occupied – trade seemingly starts and tails off very early, and Saturday and Sunday are the best and busiest days. But there were still over 200 ‘stalls’, so the hunt was on. I had a good look round first to see what items were repeated across stands – obviously these would be factory produced contemporary pieces. Almost dizzy from the enormous selection, I spotted an appealing blue and white ceramic bottle vase at one stand, and a bright, three-coloured ‘Peking glass’ vase at another.  Although I also wanted some bronze and jade, the quality of these looked either too poor or too obviously ‘old’. Plus I also collect glass, and I’ve always liked blue & white porcelain and been interested in the marks on the bases.

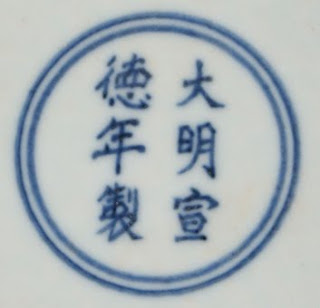

Although I also wanted some bronze and jade, the quality of these looked either too poor or too obviously ‘old’. Plus I also collect glass, and I’ve always liked blue & white porcelain and been interested in the marks on the bases.

Bartering is obligatory here. The problem is that, as this isn’t really on the main tourist trail despite the dual language signage, nobody speaks English! The universal languages of gesticulation and facial expressions come into play, along with a calculator to indicate the price.

The blue and white vase (18cm/7in high) was up first and the seller stabbed 1,200 yuan (£110/$175) into the calculator. I countered with a cheeky 120 yuan (£12/$18). In a second’s time I was given the calculator again and the new price was 900 yuan. I typed 120 yuan again. Huffing and puffing ensued and led to an offer of 600 yuan. Holding my position, I firmly retyped 120 yuan, accompanying it with a grim expression. He took the calculator back and turned his back on me with a theatrical shrug. I began to walk away. He grabbed my arm gently and thrust the calculator back in my face. The screen read 150 yuan. I smiled and took out a 100 yuan note from my back pocket and rustled a 20 yuan note out of my wallet which I had previously prepared to only contain small notes. He turned away, and I began to walk away again. This time he shouted and grabbed my arm, nodding to accept the cash. Within seconds the vase was wrapped in torn newspaper and in a plastic bag and I had handed over my cash. I guess it’s sometimes good to go late in the day, even though it was early for me!

The blue and white vase (18cm/7in high) was up first and the seller stabbed 1,200 yuan (£110/$175) into the calculator. I countered with a cheeky 120 yuan (£12/$18). In a second’s time I was given the calculator again and the new price was 900 yuan. I typed 120 yuan again. Huffing and puffing ensued and led to an offer of 600 yuan. Holding my position, I firmly retyped 120 yuan, accompanying it with a grim expression. He took the calculator back and turned his back on me with a theatrical shrug. I began to walk away. He grabbed my arm gently and thrust the calculator back in my face. The screen read 150 yuan. I smiled and took out a 100 yuan note from my back pocket and rustled a 20 yuan note out of my wallet which I had previously prepared to only contain small notes. He turned away, and I began to walk away again. This time he shouted and grabbed my arm, nodding to accept the cash. Within seconds the vase was wrapped in torn newspaper and in a plastic bag and I had handed over my cash. I guess it’s sometimes good to go late in the day, even though it was early for me!

Onto the glass vase (15cm/6in high), which was one of only two I saw in the whole place. After I pointed it out, the lady seller proudly shouted out ‘Older!’ with a grin. The calculator price was 1,800 yuan (£160/$260). Fired by my last bargain, I typed 100 yuan (£9/$15) in and unsurprisingly nearly blew the deal! After I smiled to show the game had opened, the calculator was returned with a 1,500 yuan price tag. I pushed my luck and went to 120 yuan. The next price was 920. I began to turn away and the immediate next price was 600. I tried 120 again, but was met with a serious ‘NO!’ type of expression. Clearly it was time for me to move again, so I typed 150 yuan. The deal was back on track. The price dropped again to 450 yuan, as she pointed out the birds and flowers on the vase and reiterated the ‘Older!’ exclamation. I shrugged and looked bored and the price became 300 yuan. I immediately countered with 180 yuan (£17/$26) and ran my hand firmly across my neck to show this was my final price. She barked at her colleague and within seconds the vase was wrapped in scrumpled newspaper and in a bag as she looked theatrically distraught, shaking her head. We shook hands, and vase, cash and smiles were exchanged. Wow – an intense and rapid experience again!

Onto the glass vase (15cm/6in high), which was one of only two I saw in the whole place. After I pointed it out, the lady seller proudly shouted out ‘Older!’ with a grin. The calculator price was 1,800 yuan (£160/$260). Fired by my last bargain, I typed 100 yuan (£9/$15) in and unsurprisingly nearly blew the deal! After I smiled to show the game had opened, the calculator was returned with a 1,500 yuan price tag. I pushed my luck and went to 120 yuan. The next price was 920. I began to turn away and the immediate next price was 600. I tried 120 again, but was met with a serious ‘NO!’ type of expression. Clearly it was time for me to move again, so I typed 150 yuan. The deal was back on track. The price dropped again to 450 yuan, as she pointed out the birds and flowers on the vase and reiterated the ‘Older!’ exclamation. I shrugged and looked bored and the price became 300 yuan. I immediately countered with 180 yuan (£17/$26) and ran my hand firmly across my neck to show this was my final price. She barked at her colleague and within seconds the vase was wrapped in scrumpled newspaper and in a bag as she looked theatrically distraught, shaking her head. We shook hands, and vase, cash and smiles were exchanged. Wow – an intense and rapid experience again!

We then took a calming walk around the rest of the mini-streets inside the market compound, looking into the many shops that stocked everything from Ming dynasty style furniture to yet more ceramics, bronzes and jades. Prices seemed higher, but shop owners were very keen to get bartering going by proffering calculators and motioning at pieces that I had looked at. Everyone has something to sell, and they’re admirably not shy about trying to sell it to you, showing the country’s centuries’ long experience in trading. A tip though – as with any bartering, always be polite, respectful, cheerful, gentle and show good intentions. Rudeness will get you nowhere.

We then took a calming walk around the rest of the mini-streets inside the market compound, looking into the many shops that stocked everything from Ming dynasty style furniture to yet more ceramics, bronzes and jades. Prices seemed higher, but shop owners were very keen to get bartering going by proffering calculators and motioning at pieces that I had looked at. Everyone has something to sell, and they’re admirably not shy about trying to sell it to you, showing the country’s centuries’ long experience in trading. A tip though – as with any bartering, always be polite, respectful, cheerful, gentle and show good intentions. Rudeness will get you nowhere.

By midday, the market appeared to be slowing down. A few other Westerners had arrived by taxi and browsed around. Many seemed taken by the bright, jaunty colours of the more modern pieces on offer, but a shop selling (surprisingly) apparently original gramophones, cameras and Bakelite radios also attracted plenty of attention.

As the market is somewhat out of the way, hailing a taxi back to the centre (25mins) was more of a trial than bartering. Many guide books, such as our excellent and thoroughly trustworthy Moon guide, recommend booking a car for the return trip and this seems like good advice. As we sped away to the sound of Chinese pop blaring from the radio, I though about showing my new purchases to a couple of colleagues on the Antiques Roadshow.

As the market is somewhat out of the way, hailing a taxi back to the centre (25mins) was more of a trial than bartering. Many guide books, such as our excellent and thoroughly trustworthy Moon guide, recommend booking a car for the return trip and this seems like good advice. As we sped away to the sound of Chinese pop blaring from the radio, I though about showing my new purchases to a couple of colleagues on the Antiques Roadshow.

Although I have no doubt that they are modern reproductions from the £27 ($43) total price and suspicious presence of mud on the bodies, I want to know exactly how an expert can tell, and what the marks on the bottoms (one shown above) mean. I also wonder how old they actually are? I’ll let you know when I find out. Still, none of this matters to me – both are pieces that I like, and they make affordable souvenirs of a highly memorable experience.

Although I have no doubt that they are modern reproductions from the £27 ($43) total price and suspicious presence of mud on the bodies, I want to know exactly how an expert can tell, and what the marks on the bottoms (one shown above) mean. I also wonder how old they actually are? I’ll let you know when I find out. Still, none of this matters to me – both are pieces that I like, and they make affordable souvenirs of a highly memorable experience.